🤗 트랜스포머 및 TPU를 사용하여 처음부터 언어 모델 트레이닝하기

- 원본 링크 : https://keras.io/examples/nlp/mlm_training_tpus/

- 최종 확인 : 2024-11-21

저자 : Matthew Carrigan, Sayak Paul

생성일 : 2023/05/21

최종 편집일 : 2023/05/21

설명 : Train a masked language model on TPUs using 🤗 Transformers.

Introduction

In this example, we cover how to train a masked language model using TensorFlow, 🤗 Transformers, and TPUs.

TPU training is a useful skill to have: TPU pods are high-performance and extremely scalable, making it easy to train models at any scale from a few tens of millions of parameters up to truly enormous sizes: Google’s PaLM model (over 500 billion parameters!) was trained entirely on TPU pods.

We’ve previously written a tutorial and a Colab example showing small-scale TPU training with TensorFlow and introducing the core concepts you need to understand to get your model working on TPU. However, our Colab example doesn’t contain all the steps needed to train a language model from scratch such as training the tokenizer. So, we wanted to provide a consolidated example of walking you through every critical step involved there.

As in our Colab example, we’re taking advantage of TensorFlow’s very clean TPU support via XLA and TPUStrategy. We’ll also be benefiting from the fact that the majority of the TensorFlow models in 🤗 Transformers are fully XLA-compatible. So surprisingly, little work is needed to get them to run on TPU.

This example is designed to be scalable and much closer to a realistic training run – although we only use a BERT-sized model by default, the code could be expanded to a much larger model and a much more powerful TPU pod slice by changing a few configuration options.

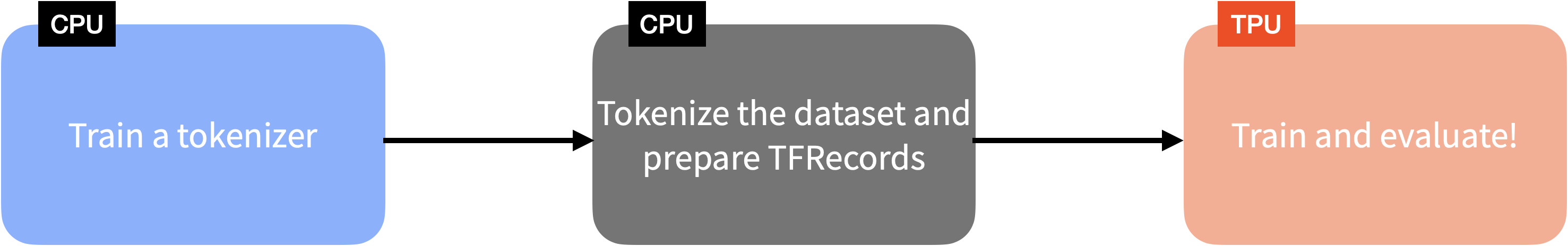

The following diagram gives you a pictorial overview of the steps involved in training a language model with 🤗 Transformers using TensorFlow and TPUs:

(Contents of this example overlap with this blog post).

Data

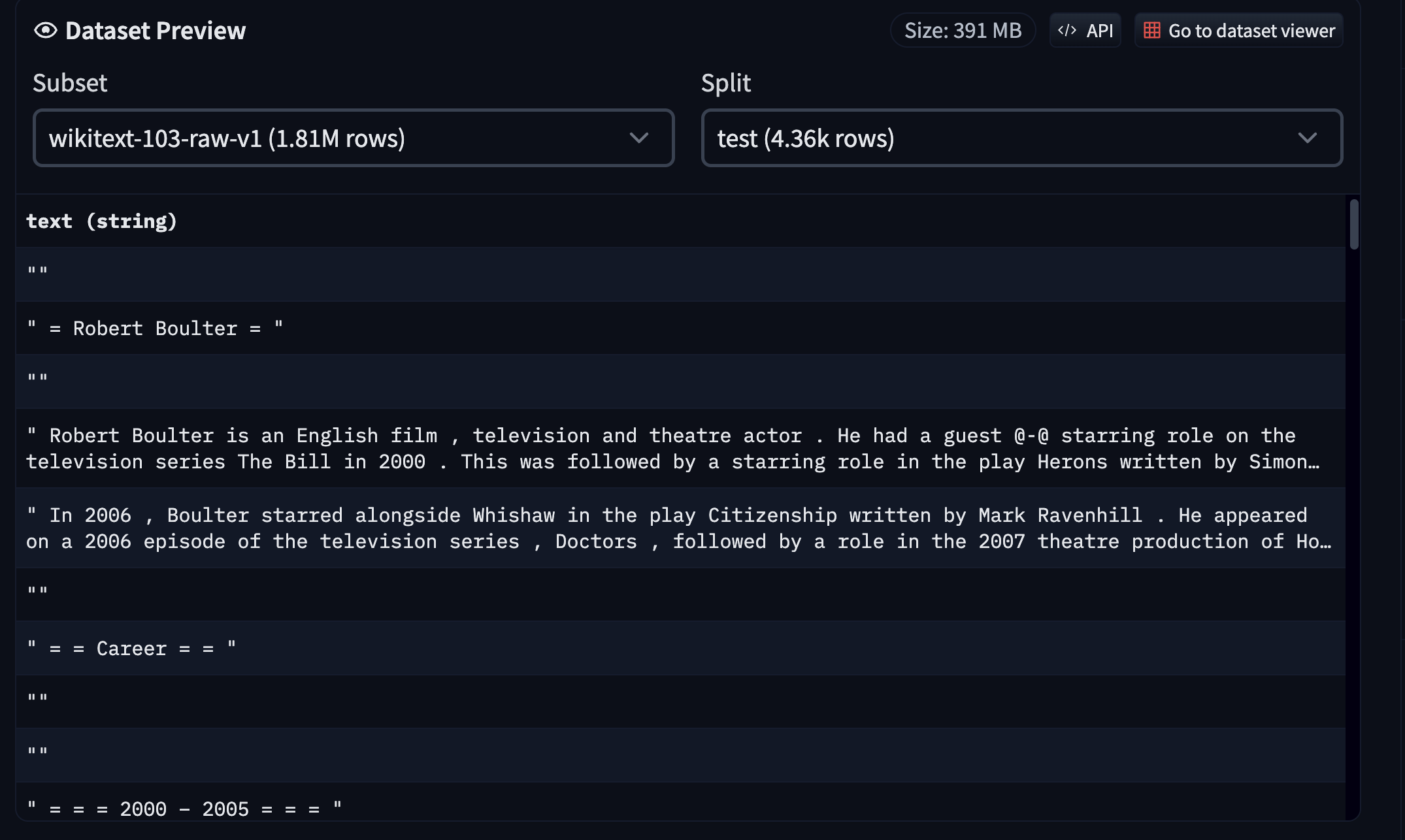

We use the WikiText dataset (v1). You can head over to the dataset page on the Hugging Face Hub to explore the dataset.

Since the dataset is already available on the Hub in a compatible format, we can easily load and interact with it using 🤗 datasets. However, training a language model from scratch also requires a separate tokenizer training step. We skip that part in this example for brevity, but, here’s a gist of what we can do to train a tokenizer from scratch:

- Load the

trainsplit of the WikiText using 🤗 datasets. - Leverage 🤗 tokenizers to train a Unigram model.

- Upload the trained tokenizer on the Hub.

You can find the tokenizer training code here and the tokenizer here. This script also allows you to run it with any compatible dataset from the Hub.

Tokenizing the data and creating TFRecords

Once the tokenizer is trained, we can use it on all the dataset splits (train, validation, and test in this case) and create TFRecord shards out of them. Having the data splits spread across multiple TFRecord shards helps with massively parallel processing as opposed to having each split in single TFRecord files.

We tokenize the samples individually. We then take a batch of samples, concatenate them together, and split them into several chunks of a fixed size (128 in our case). We follow this strategy rather than tokenizing a batch of samples with a fixed length to avoid aggressively discarding text content (because of truncation).

We then take these tokenized samples in batches and serialize those batches as multiple TFRecord shards, where the total dataset length and individual shard size determine the number of shards. Finally, these shards are pushed to a Google Cloud Storage (GCS) bucket.

If you’re using a TPU node for training, then the data needs to be streamed from a GCS bucket since the node host memory is very small. But for TPU VMs, we can use datasets locally or even attach persistent storage to those VMs. Since TPU nodes (which is what we have in a Colab) are still quite heavily used, we based our example on using a GCS bucket for data storage.

You can see all of this in code in this script. For convenience, we have also hosted the resultant TFRecord shards in this repository on the Hub.

Once the data is tokenized and serialized into TFRecord shards, we can proceed toward training.

Training

Setup and imports

Let’s start by installing 🤗 Transformers.

!pip install transformers -qThen, let’s import the modules we need.

import os

import re

import tensorflow as tf

import transformersInitialize TPUs

Then let’s connect to our TPU and determine the distribution strategy:

tpu = tf.distribute.cluster_resolver.TPUClusterResolver()

tf.config.experimental_connect_to_cluster(tpu)

tf.tpu.experimental.initialize_tpu_system(tpu)

strategy = tf.distribute.TPUStrategy(tpu)

print(f"Available number of replicas: {strategy.num_replicas_in_sync}")결과

Available number of replicas: 8We then load the tokenizer. For more details on the tokenizer, check out its repository. For the model, we use RoBERTa (the base variant), introduced in this paper.

Initialize the tokenizer

tokenizer = "tf-tpu/unigram-tokenizer-wikitext"

pretrained_model_config = "roberta-base"

tokenizer = transformers.AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(tokenizer)

config = transformers.AutoConfig.from_pretrained(pretrained_model_config)

config.vocab_size = tokenizer.vocab_size결과

Downloading (…)okenizer_config.json: 0%| | 0.00/483 [00:00<?, ?B/s]

Downloading (…)/main/tokenizer.json: 0%| | 0.00/1.61M [00:00<?, ?B/s]

Downloading (…)cial_tokens_map.json: 0%| | 0.00/286 [00:00<?, ?B/s]

Downloading (…)lve/main/config.json: 0%| | 0.00/481 [00:00<?, ?B/s]Prepare the datasets

We now load the TFRecord shards of the WikiText dataset (which the Hugging Face team prepared beforehand for this example):

train_dataset_path = "gs://tf-tpu-training-resources/train"

eval_dataset_path = "gs://tf-tpu-training-resources/validation"

training_records = tf.io.gfile.glob(os.path.join(train_dataset_path, "*.tfrecord"))

eval_records = tf.io.gfile.glob(os.path.join(eval_dataset_path, "*.tfrecord"))Now, we will write a utility to count the number of training samples we have. We need to know this value in order properly initialize our optimizer later:

def count_samples(file_list):

num_samples = 0

for file in file_list:

filename = file.split("/")[-1]

sample_count = re.search(r"-\d+-(\d+)\.tfrecord", filename).group(1)

sample_count = int(sample_count)

num_samples += sample_count

return num_samples

num_train_samples = count_samples(training_records)

print(f"Number of total training samples: {num_train_samples}")결과

Number of total training samples: 300917Let’s now prepare our datasets for training and evaluation. We start by writing our utilities. First, we need to be able to decode the TFRecords:

max_sequence_length = 512

def decode_fn(example):

features = {

"input_ids": tf.io.FixedLenFeature(

dtype=tf.int64, shape=(max_sequence_length,)

),

"attention_mask": tf.io.FixedLenFeature(

dtype=tf.int64, shape=(max_sequence_length,)

),

}

return tf.io.parse_single_example(example, features)Here, max_sequence_length needs to be the same as the one used during preparing the TFRecord shards.Refer to this script for more details.

Next up, we have our masking utility that is responsible for masking parts of the inputs and preparing labels for the masked language model to learn from. We leverage the DataCollatorForLanguageModeling for this purpose.

# We use a standard masking probability of 0.15. `mlm_probability` denotes

# probability with which we mask the input tokens in a sequence.

mlm_probability = 0.15

data_collator = transformers.DataCollatorForLanguageModeling(

tokenizer=tokenizer, mlm_probability=mlm_probability, mlm=True, return_tensors="tf"

)

def mask_with_collator(batch):

special_tokens_mask = (

~tf.cast(batch["attention_mask"], tf.bool)

| (batch["input_ids"] == tokenizer.cls_token_id)

| (batch["input_ids"] == tokenizer.sep_token_id)

)

batch["input_ids"], batch["labels"] = data_collator.tf_mask_tokens(

batch["input_ids"],

vocab_size=len(tokenizer),

mask_token_id=tokenizer.mask_token_id,

special_tokens_mask=special_tokens_mask,

)

return batchAnd now is the time to write the final data preparation utility to put it all together in a tf.data.Dataset object:

auto = tf.data.AUTOTUNE

shuffle_buffer_size = 2**18

def prepare_dataset(

records, decode_fn, mask_fn, batch_size, shuffle, shuffle_buffer_size=None

):

num_samples = count_samples(records)

dataset = tf.data.Dataset.from_tensor_slices(records)

if shuffle:

dataset = dataset.shuffle(len(dataset))

dataset = tf.data.TFRecordDataset(dataset, num_parallel_reads=auto)

# TF can't infer the total sample count because it doesn't read

# all the records yet, so we assert it here.

dataset = dataset.apply(tf.data.experimental.assert_cardinality(num_samples))

dataset = dataset.map(decode_fn, num_parallel_calls=auto)

if shuffle:

assert shuffle_buffer_size is not None

dataset = dataset.shuffle(shuffle_buffer_size)

dataset = dataset.batch(batch_size, drop_remainder=True)

dataset = dataset.map(mask_fn, num_parallel_calls=auto)

dataset = dataset.prefetch(auto)

return datasetLet’s prepare our datasets with these utilities:

per_replica_batch_size = 16 # Change as needed.

batch_size = per_replica_batch_size * strategy.num_replicas_in_sync

shuffle_buffer_size = 2**18 # Default corresponds to a 1GB buffer for seq_len 512

train_dataset = prepare_dataset(

training_records,

decode_fn=decode_fn,

mask_fn=mask_with_collator,

batch_size=batch_size,

shuffle=True,

shuffle_buffer_size=shuffle_buffer_size,

)

eval_dataset = prepare_dataset(

eval_records,

decode_fn=decode_fn,

mask_fn=mask_with_collator,

batch_size=batch_size,

shuffle=False,

)Let’s now investigate how a single batch of dataset looks like.

single_batch = next(iter(train_dataset))

print(single_batch.keys())결과

dict_keys(['attention_mask', 'input_ids', 'labels'])input_idsdenotes the tokenized versions of the input samples containing the mask tokens as well.attention_maskdenotes the mask to be used when performing attention operations.labelsdenotes the actual values of masked tokens the model is supposed to learn from.

for k in single_batch:

if k == "input_ids":

input_ids = single_batch[k]

print(f"Input shape: {input_ids.shape}")

if k == "labels":

labels = single_batch[k]

print(f"Label shape: {labels.shape}")결과

Input shape: (128, 512)

Label shape: (128, 512)Now, we can leverage our tokenizer to investigate the values of the tokens. Let’s start with input_ids:

idx = 0

print("Taking the first sample:\n")

print(tokenizer.decode(input_ids[idx].numpy()))결과

Taking the first sample:they called the character of Tsugum[MASK] one of the[MASK] tragic heroines[MASK] had encountered in a game. Chandran ranked the game as the third best role @[MASK][MASK] playing game from the sixth generation of video[MASK] consoles, saying that it was his favorite in the[MASK]Infinity[MASK], and one his favorite[MASK] games overall[MASK].[MASK]

[SEP][CLS][SEP][CLS][SEP][CLS] =[MASK] Sea party 1914[MASK]– 16 =

[SEP][CLS][SEP][CLS] The Ross Sea party was a component of Sir[MASK] Shackleton's Imperial Trans @-@ Antarctic Expedition 1914 garde 17.[MASK] task was to lay a series of supply depots across the Great Ice Barrier from the Ross Sea to the Beardmore Glacier, along the[MASK] route established by earlier Antarctic expeditions[MASK]. The expedition's main party, under[MASK], was to land[MASK]on the opposite, Weddell Sea coast of Antarctica [MASK] and to march across the continent via the South[MASK] to the Ross Sea. As the main party would be un[MASK] to carry[MASK] fuel and supplies for the whole distance[MASK], their survival depended on the Ross Sea party's depots[MASK][MASK][MASK] would cover the[MASK] quarter of their journey.

[SEP][CLS][MASK] set sail from London on[MASK] ship Endurance, bound[MASK] the Weddell Sea in August 1914. Meanwhile, the Ross Sea party[MASK] gathered in Australia, prior[MASK] Probabl for the Ross Sea in[MASK] second expedition ship, SY Aurora. Organisational and financial problems[MASK]ed their[MASK] until December 1914, which shortened their first depot @-@[MASK] season.[MASK][MASK] arrival the inexperienced party struggle[MASK] to master the art of Antarctic travel, in the[MASK] losing most of their sledge dogs [MASK]อ greater misfortune[MASK]ed when, at the onset of the southern winter, Aurora[MASK] torn from its [MASK]ings during [MASK] severe storm and was un[MASK] to return, leaving the shore party stranded.

[SEP][CLS] Crossroadspite[MASK] setbacks, the Ross Sea party survived inter @-@ personnel disputes, extreme weather[MASK], illness, and Pay deaths of three of its members to carry[MASK] its[MASK] in full during its[MASK] Antarctic season. This success proved ultimate[MASK] without purpose, because Shackleton's Grimaldi expedition was unAs expected, the decoded tokens contain the special tokens including the mask tokens as well. Let’s now investigate the mask tokens:

# Taking the first 30 tokens of the first sequence.

print(labels[0].numpy()[:30])결과

[-100 -100 -100 -100 -100 -100 -100 -100 -100 43 -100 -100 -100 -100

351 -100 -100 -100 99 -100 -100 -100 -100 -100 -100 -100 -100 -100

-100 -100]Here, -100 means that the corresponding tokens in the input_ids are NOT masked and non -100 values denote the actual values of the masked tokens.

Initialize the mode and and the optimizer

With the datasets prepared, we now initialize and compile our model and optimizer within the strategy.scope():

# For this example, we keep this value to 10. But for a realistic run, start with 500.

num_epochs = 10

steps_per_epoch = num_train_samples // (

per_replica_batch_size * strategy.num_replicas_in_sync

)

total_train_steps = steps_per_epoch * num_epochs

learning_rate = 0.0001

weight_decay_rate = 1e-3

with strategy.scope():

model = transformers.TFAutoModelForMaskedLM.from_config(config)

model(

model.dummy_inputs

) # Pass some dummy inputs through the model to ensure all the weights are built

optimizer, schedule = transformers.create_optimizer(

num_train_steps=total_train_steps,

num_warmup_steps=total_train_steps // 20,

init_lr=learning_rate,

weight_decay_rate=weight_decay_rate,

)

model.compile(optimizer=optimizer, metrics=["accuracy"])결과

No loss specified in compile() - the model's internal loss computation will be used as the loss. Don't panic - this is a common way to train TensorFlow models in Transformers! To disable this behaviour please pass a loss argument, or explicitly pass `loss=None` if you do not want your model to compute a loss.A couple of things to note here: * The create_optimizer() function creates an Adam optimizer with a learning rate schedule using a warmup phase followed by a linear decay. Since we’re using weight decay here, under the hood, create_optimizer() instantiates the right variant of Adam to enable weight decay. * While compiling the model, we’re NOT using any loss argument. This is because the TensorFlow models internally compute the loss when expected labels are provided. Based on the model type and the labels being used, transformers will automatically infer the loss to use.

Start training!

Next, we set up a handy callback to push the intermediate training checkpoints to the Hugging Face Hub. To be able to operationalize this callback, we need to log in to our Hugging Face account (if you don’t have one, you create one here for free). Execute the code below for logging in:

from huggingface_hub import notebook_login

notebook_login()Let’s now define the PushToHubCallback:

hub_model_id = output_dir = "masked-lm-tpu"

callbacks = []

callbacks.append(

transformers.PushToHubCallback(

output_dir=output_dir, hub_model_id=hub_model_id, tokenizer=tokenizer

)

)결과

Cloning https://huggingface.co/sayakpaul/masked-lm-tpu into local empty directory.

WARNING:huggingface_hub.repository:Cloning https://huggingface.co/sayakpaul/masked-lm-tpu into local empty directory.

Download file tf_model.h5: 0%| | 15.4k/477M [00:00<?, ?B/s]

Clean file tf_model.h5: 0%| | 1.00k/477M [00:00<?, ?B/s]And now, we’re ready to chug the TPUs:

# In the interest of the runtime of this example,

# we limit the number of batches to just 2.

model.fit(

train_dataset.take(2),

validation_data=eval_dataset.take(2),

epochs=num_epochs,

callbacks=callbacks,

)

# After training we also serialize the final model.

model.save_pretrained(output_dir)결과

Epoch 1/10

2/2 [==============================] - 96s 35s/step - loss: 10.2116 - accuracy: 0.0000e+00 - val_loss: 10.1957 - val_accuracy: 2.2888e-05

Epoch 2/10

2/2 [==============================] - 9s 2s/step - loss: 10.2017 - accuracy: 0.0000e+00 - val_loss: 10.1798 - val_accuracy: 0.0000e+00

Epoch 3/10

2/2 [==============================] - ETA: 0s - loss: 10.1890 - accuracy: 7.6294e-06

WARNING:tensorflow:Callback method `on_train_batch_end` is slow compared to the batch time (batch time: 0.0045s vs `on_train_batch_end` time: 9.1679s). Check your callbacks.

2/2 [==============================] - 35s 27s/step - loss: 10.1890 - accuracy: 7.6294e-06 - val_loss: 10.1604 - val_accuracy: 1.5259e-05

Epoch 4/10

2/2 [==============================] - 8s 2s/step - loss: 10.1733 - accuracy: 1.5259e-05 - val_loss: 10.1145 - val_accuracy: 7.6294e-06

Epoch 5/10

2/2 [==============================] - 34s 26s/step - loss: 10.1336 - accuracy: 1.5259e-05 - val_loss: 10.0666 - val_accuracy: 7.6294e-06

Epoch 6/10

2/2 [==============================] - 10s 2s/step - loss: 10.0906 - accuracy: 6.1035e-05 - val_loss: 10.0200 - val_accuracy: 5.4169e-04

Epoch 7/10

2/2 [==============================] - 33s 25s/step - loss: 10.0360 - accuracy: 6.1035e-04 - val_loss: 9.9646 - val_accuracy: 0.0049

Epoch 8/10

2/2 [==============================] - 8s 2s/step - loss: 9.9830 - accuracy: 0.0038 - val_loss: 9.8938 - val_accuracy: 0.0155

Epoch 9/10

2/2 [==============================] - 33s 26s/step - loss: 9.9067 - accuracy: 0.0116 - val_loss: 9.8225 - val_accuracy: 0.0198

Epoch 10/10

2/2 [==============================] - 8s 2s/step - loss: 9.8302 - accuracy: 0.0196 - val_loss: 9.7454 - val_accuracy: 0.0215Once your training is complete, you can easily perform inference like so:

from transformers import pipeline

# Replace your `model_id` here.

# Here, we're using a model that the Hugging Face team trained for longer.

model_id = "tf-tpu/roberta-base-epochs-500-no-wd"

unmasker = pipeline("fill-mask", model=model_id, framework="tf")

print(unmasker("Goal of my life is to [MASK]."))결과

Downloading (…)lve/main/config.json: 0%| | 0.00/649 [00:00<?, ?B/s]

Downloading tf_model.h5: 0%| | 0.00/500M [00:00<?, ?B/s]

All model checkpoint layers were used when initializing TFRobertaForMaskedLM.All the layers of TFRobertaForMaskedLM were initialized from the model checkpoint at tf-tpu/roberta-base-epochs-500-no-wd.

If your task is similar to the task the model of the checkpoint was trained on, you can already use TFRobertaForMaskedLM for predictions without further training.

Downloading (…)okenizer_config.json: 0%| | 0.00/683 [00:00<?, ?B/s]

Downloading (…)/main/tokenizer.json: 0%| | 0.00/1.61M [00:00<?, ?B/s]

Downloading (…)cial_tokens_map.json: 0%| | 0.00/286 [00:00<?, ?B/s]

[{'score': 0.10031876713037491, 'token': 52, 'token_str': 'be', 'sequence': 'Goal of my life is to be.'}, {'score': 0.032648470252752304, 'token': 5, 'token_str': '', 'sequence': 'Goal of my life is to .'}, {'score': 0.02152678370475769, 'token': 138, 'token_str': 'work', 'sequence': 'Goal of my life is to work.'}, {'score': 0.019547568634152412, 'token': 984, 'token_str': 'act', 'sequence': 'Goal of my life is to act.'}, {'score': 0.01939115859568119, 'token': 73, 'token_str': 'have', 'sequence': 'Goal of my life is to have.'}]And that’s it!

If you enjoyed this example, we encourage you to check out the full codebase here and the accompanying blog post here.